Music is an

art form whose

medium is

sound. Its common elements are

pitch (which governs

melody and

harmony),

rhythm (and its associated concepts

tempo,

meter, and

articulation),

dynamics, and the sonic qualities of

timbre and

texture. The word derives from

Greek μουσική (

mousike; "art of the

Muses").

[1]

In its most general form the activities describing music as an art form

include the production of works of music, the criticism of music, the

study of the history of music, and the aesthetic dissemination of music.

The creation,

performance, significance, and even the

definition of music

vary according to culture and social context. Music ranges from

strictly organized compositions (and their recreation in performance),

through improvisational music to

aleatoric forms. Music can be divided into

genres and

subgenres,

although the dividing lines and relationships between music genres are

often subtle, sometimes open to personal interpretation, and

occasionally controversial. Within

the arts, music may be classified as a

performing art, a

fine art, and auditory art. It may also be divided among

art music and

folk music. There is also a strong connection between

music and mathematics.

[2] Music may be played and heard live, may be part of a

dramatic work or

film, or may be recorded.

To many people in many cultures, music is an important part of their way of life.

Ancient Greek and

Indian philosophers

defined music as tones ordered horizontally as melodies and vertically

as harmonies. Common sayings such as "the harmony of the spheres" and

"it is music to my ears" point to the notion that music is often ordered

and pleasant to listen to. However, 20th-century composer

John Cage thought that any sound can be music, saying, for example, "There is no noise, only sound."

[3]

Music as form of art

Jean-Gabriel Ferlan performing at a 2008 concert at the collège-lycée Saint-François Xavier

Music is composed and performed for many purposes, ranging from aesthetic pleasure, religious or ceremonial purposes, or as an

entertainment

product for the marketplace. As the poet and essayist Geoffrey O'Brien

notes, mix tapes are an art form in themselves, a "self-portrait, a

gesture of friendship, prescription for an ideal party... an environment

consisting solely of what is most ardently loved.".

[4]

Amateur musicians compose and perform music for their own pleasure, and

they do not derive their income from music. Professional musicians are

employed by a range of institutions and organisations, including armed

forces, churches and synagogues, symphony orchestras,

broadcasting or

film production companies, and

music schools. Professional musicians sometimes work as freelancers, seeking contracts and engagements in a variety of settings.

There are often many links between amateur and professional musicians. Beginning amateur musicians take

lessons

with professional musicians. In community settings, advanced amateur

musicians perform with professional musicians in a variety of ensembles,

such as

concert bands,

orchestras,

and other ensembles. In some cases, amateur musicians attain a

professional level of competence, and they are able to perform in

professional performance settings. A distinction is often made between

music performed for the benefit of a live audience and music that is

performed for the purpose of being recorded and distributed through the

music retail system or the broadcasting system. However, there are also

many cases where a live performance in front of an audience is recorded

and distributed (or broadcast).

Composition

"Composition" is often classed as the creation and recording of music

via a medium by which others can interpret it (i.e., paper or sound).

Many cultures use at least part of the concept of preconceiving musical

material, or composition, as held in western

classical music.

Even when music is notated precisely, there are still many decisions

that a performer has to make. The process of a performer deciding how to

perform music that has been previously composed and notated is termed

interpretation. Different performers' interpretations of the same music

can vary widely. Composers and song writers who present their own music

are interpreting, just as much as those who perform the music of others

or folk music. The standard body of choices and techniques present at a

given time and a given place is referred to as

performance practice,

whereas interpretation is generally used to mean either individual

choices of a performer, or an aspect of music that is not clear, and

therefore has a "standard" interpretation.

In some musical genres, such as jazz and blues, even more freedom is

given to the performer to engage in improvisation on a basic melodic,

harmonic, or rhythmic framework. The greatest latitude is given to the

performer in a style of performing called

free improvisation, which is material that is spontaneously "thought of" (imagined) while being performed,

not preconceived. Improvised music usually follows stylistic or genre conventions and even "fully composed" includes some

freely chosen material.

Composition does not always mean the use of notation, or the known sole

authorship of one individual. Music can also be determined by

describing a "process" that creates musical sounds. Examples of this

range from wind chimes, through computer programs that select sounds.

Music from random elements is called

Aleatoric music, and is associated with such composers as John Cage,

Morton Feldman, and

Witold Lutosławski.

Music can be composed for repeated performance or it can be

improvised: composed on the spot. The music can be performed entirely

from memory, from a written system of musical notation, or some

combination of both. Study of composition has traditionally been

dominated by examination of methods and practice of Western classical

music, but the definition of composition is broad enough to include

spontaneously improvised works like those of

free jazz performers and African drummers such as the

Ewe drummers.

Notation

Sheet music is written representation of music. This is a

homorhythmic (i.e.,

hymn-style) arrangement of a traditional piece entitled "

Adeste Fideles", in standard two-staff format for mixed voices.

Play (help·info)

Play (help·info)

Notation is the written expression of music notes and rhythms on

paper using symbols. When music is written down, the pitches and rhythm

of the music is notated, along with instructions on how to perform the

music. The study of how to read notation involves music theory, harmony,

the study of performance practice, and in some cases an understanding

of historical performance methods. Written notation varies with style

and period of music. In Western Art music, the most common types of

written notation are scores, which include all the music parts of an

ensemble piece, and parts, which are the music notation for the

individual performers or singers. In popular music, jazz, and blues, the

standard musical notation is the lead sheet, which notates the melody,

chords,

lyrics

(if it is a vocal piece), and structure of the music. Scores and parts

are also used in popular music and jazz, particularly in large ensembles

such as jazz "big bands."

In popular music,

guitarists and electric

bass

players often read music notated in tablature (often abbreviated as

"tab"), which indicates the location of the notes to be played on the

instrument using a diagram of the guitar or bass fingerboard. Tabulature

was also used in the Baroque era to notate music for the

lute, a stringed, fretted instrument. Notated music is produced as

sheet music.

To perform music from notation requires an understanding of both the

rhythmic and pitch elements embodied in the symbols and the performance

practice that is associated with a piece of music or a genre. In

improvisation, the performer often plays from music where only the chord

changes are written, requiring a great understanding of the music's

structure and

chord progressions.

Improvisation

Musical improvisation

is the creation of spontaneous music. Improvisation is often considered

an act of instantaneous composition by performers, where compositional

techniques are employed with or without preparation. Improvisation is a

major part of some types of music, such as

blues,

jazz, and

jazz fusion,

in which instrumental performers improvise solos and melody lines. In

the Western art music tradition, improvisation was an important skill

during the Baroque era and during the Classical era; solo performers and

singers improvised virtuoso cadenzas during concerts. However, in the

20th and early 21st century, as "common practice" western

art music

performance became institutionalized in symphony orchestras, opera

houses and ballets, improvisation has played a smaller role at the same

time that many

composers

increasingly returned to its inclusion in their creative work. In

Indian classical music, spontaneous improvisation is a core component

and an essential criteria of any performance.

Theory

Main article:

Music theory

Music theory encompasses the nature and mechanics of music. It often

involves identifying patterns that govern composers' techniques and

examining the

language and

notation of music. In a grand sense, music theory distills and analyzes the

parameters or elements of music –

rhythm,

harmony (

harmonic function),

melody,

structure,

form, and

texture. Broadly, music theory may include any statement, belief, or conception of or about music.

[5] People who study these properties are known as music theorists. Some have applied

acoustics,

human physiology, and

psychology to the explanation of how and why music is

perceived.

Music has many different fundamentals or elements. These are, but are

not limited to: pitch, beat or pulse, rhythm, melody, harmony, texture,

allocation of voices, timbre or color, expressive qualities (dynamics

and articulation), and form or structure.

Pitch is a subjective sensation, reflecting generally the lowness or highness of a sound.

Rhythm is the arrangement of sounds and silences in

time.

Meter animates time in regular pulse groupings, called

measures or bars.

A melody is a series of notes sounding in succession. The notes of a

melody are typically created with respect to pitch systems such as

scales or

modes.

Harmony

is the study of vertical sonorities in music. Vertical sonority refers

to considering the relationships between pitches that occur together;

usually this means at the same time, although harmony can also be

implied by a melody that outlines a harmonic structure. Notes can be

arranged into different

scales and

modes.

Western music theory generally divides the octave into a series of 12

notes that might be included in a piece of music. In music written using

the system of major-minor

tonality, the

key of a piece determines the scale used.

Musical texture

is the overall sound of a piece of music commonly described according

to the number of and relationship between parts or lines of music:

monophony,

heterophony,

polyphony,

homophony, or

monody.

Timbre, sometimes called "Color" or "Tone Color" is the quality or sound of a voice or instrument.

[6]

Expressive Qualities are those elements in music that create change in

music that are not related to pitch, rhythm or timbre. They include

Dynamics and Articulation.

Form

is a facet of music theory that explores the concept of musical syntax,

on a local and global level. Examples of common forms of Western music

include the

fugue, the

invention,

sonata-allegro,

canon,

strophic,

theme and variations, and

rondo. Popular Music often makes use of

strophic form often in conjunction with

Twelve bar blues. Analysis is the effort to describe and explain music.

History

Prehistoric eras

Prehistoric music can only be theorized based on findings from

paleolithic archaeology sites.

Flutes

are often discovered, carved from bones in which lateral holes have

been pierced; these are thought to have been blown at one end like the

Japanese

shakuhachi. The

Divje Babe flute, carved from a

cave bear femur, is thought to be at least 40,000 years old. Instruments such as the seven-holed flute and various types of

stringed instruments, such as the

Ravanahatha, have been recovered from the

Indus Valley Civilization archaeological sites.

[7] India has one of the oldest musical traditions in the world—references to

Indian classical music (

marga) are found in the

Vedas, ancient scriptures of the

Hindu tradition.

[8] The earliest and largest collection of prehistoric musical instruments was found in

China and dates back to between 7000 and 6600 BC.

[9] The

Hurrian song, found on

clay tablets that date back to approximately 1400 BC, is the oldest surviving notated work of music.

Ancient Egypt

Main article:

Music of Egypt

The ancient

Egyptians credited one of their gods,

Thoth, with the invention of music, with

Osiris

in turn used as part of his effort to civilize the world. The earliest

material and representational evidence of Egyptian musical instruments

dates to the

Predynastic period, but the evidence is more securely attested in the

Old Kingdom when

harps,

flutes and

double clarinets were played.

[10] Percussion instruments,

lyres and

lutes were added to orchestras by the

Middle Kingdom.

Cymbals[11] frequently accompanied music and dance, much as they still do in

Egypt today. Egyptian

folk music, including the traditional

Sufi dhikr rituals, are the closest contemporary

music genre to

ancient Egyptian music, having preserved many of its features, rhythms and instruments.

[12][13]

Asian cultures

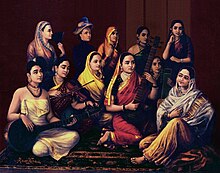

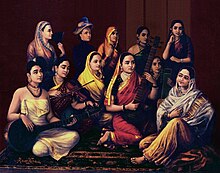

Indian women dressed in regional attire playing a variety of musical instruments popular in different parts of India

Indian classical music is one of the oldest musical traditions in the world.

[14] The

Indus Valley civilization has sculptures that show dance

[15]

and old musical instruments, like the seven holed flute. Various types

of stringed instruments and drums have been recovered from

Harrappa and

Mohenjo Daro by excavations carried out by Sir

Mortimer Wheeler.

[16] The

Rigveda has elements of present Indian music, with a musical notation to denote the metre and the mode of chanting.

[17] Indian classical music (marga) is monophonic, and based on a single melody line or

raga rhythmically organized through

talas.

Silappadhikaram by Ilango Adigal gives so much information about how new scale can be formed by modal shift of tonic from existing scale.[18]

Hindustani music was influenced by the Persian performance practices of

the Afghan Mughals. Carnatic music popular in the southern states, is

largely devotional; the majority of the songs are addressed to the Hindu

deities. There are a lot of songs emphasising love and other social

issues.

Asian music covers the music cultures of

Arabia,

Central Asia,

East Asia,

South Asia, and

Southeast Asia.

Chinese classical music,

the traditional art or court music of China, has a history stretching

over around three thousand years. It has its own unique systems of

musical notation, as well as musical tuning and pitch, musical

instruments and styles or musical genres. Chinese music is

pentatonic-diatonic, having a scale of twelve notes to an octave

(5 + 7 = 12) as does European-influenced music.

Persian music is the music of

Persia and Persian language countries:

musiqi, the science and art of music, and

muzik, the sound and performance of music (Sakata 1983).

References in the Bible

Music and theatre scholars studying the history and anthropology of

Semitic and early

Judeo-Christian culture have discovered common links in theatrical and musical activity between the classical cultures of the

Hebrews and those of later

Greeks and

Romans. The common area of performance is found in a "social phenomenon called

litany," a form of prayer consisting of a series of

invocations or

supplications.

The Journal of Religion and Theatre notes that among the earliest forms of litany, "Hebrew litany was accompanied by a rich musical tradition:"

[19]

- "While Genesis 4.21 identifies Jubal as the "father of all such as

handle the harp and pipe," the Pentateuch is nearly silent about the

practice and instruction of music in the early life of Israel. Then, in I

Samuel 10 and the texts that follow, a curious thing happens. "One

finds in the biblical text," writes Alfred Sendrey, "a sudden and

unexplained upsurge of large choirs and orchestras, consisting of

thoroughly organized and trained musical groups, which would be

virtually inconceivable without lengthy, methodical preparation." This

has led some scholars to believe that the prophet Samuel was the

patriarch of a school, which taught not only prophets and holy men, but

also sacred-rite musicians. This public music school, perhaps the

earliest in recorded history, was not restricted to a priestly

class—which is how the shepherd boy David appears on the scene as a

minstrel to King Saul."[19]

Antiquity

Western cultures

have had a major influence on the development of music. The history of

the music of the Western cultures can be traced back to Ancient Greece

times.

Ancient Greece

Music was an important part of social and cultural life in

Ancient Greece. Musicians and

singers played a prominent role in

Greek theater.

[20] Mixed-gender

choruses performed for entertainment, celebration, and spiritual ceremonies.

[21] Instruments included the double-reed

aulos and a plucked

string instrument, the

lyre, principally the special kind called a

kithara.

Music

was an important part of education, and boys were taught music starting

at age six. Greek musical literacy created a flowering of music

development. Greek

music theory included the Greek

musical modes, that eventually became the basis for Western

religious and

classical music. Later, influences from the

Roman Empire,

Eastern Europe, and the

Byzantine Empire changed Greek music. The

Seikilos epitaph is the oldest surviving example of a complete musical composition, including musical notation, from anywhere in the world.

The Middle Ages

The

medieval era (476 to 1400) started with the introduction of chanting into

Roman Catholic Church

services. Western Music then started becoming more of an art form with

the advances in music notation. The only European Medieval repertory

that survives from before about 800 is the

monophonic liturgical plainsong of the Roman Catholic Church, the central tradition of which was called

Gregorian chant. Alongside these traditions of

sacred and

church music there existed a vibrant tradition of

secular song. Examples of composers from this period are

Léonin,

Pérotin and

Guillaume de Machaut.

The Renaissance

Renaissance music (c. 1400 to 1600) was more focused on secular themes. Around 1450, the

printing

press was invented, and that helped to disseminate musical styles more

quickly and across a larger area. Thus, music could play an increasingly

important role in daily life. Musicians worked for the church, courts

and towns. Church choirs grew in size, and the church remained an

important patron of music. By the middle of the 15th century,

composers wrote richly polyphonic sacred music. Prominent composers from this era are

Guillaume Dufay,

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina,

Thomas Morley, and

Orlande de Lassus. However, musical activity shifted to the courts. Kings and princes competed for the finest composers.

Many leading important composers came from the Netherlands, Belgium,

and northern France and are called the Franco-Flemish composers. They

held important positions throughout Europe, especially in Italy. Other

countries with vibrant musical lives include Germany, England, and

Spain.

The Baroque

The

Baroque era of music took place from 1600 to 1750, as the

Baroque artistic style flourished across Europe; and during this time, music expanded in its range and complexity. Baroque music began when the first

operas were written and when

contrapuntal music became prevalent. German Baroque composers wrote for small

ensembles including strings,

brass, and

woodwinds, as well as

choirs,

pipe organ,

harpsichord, and

clavichord.

During this period several major music forms were defined that lasted

into later periods when they were expanded and evolved further,

including the

fugue, the

invention, the

sonata, and the

concerto.

[22]

The late Baroque style was polyphonically complex and ornamental and

rich in its melodies. Composers from the Baroque era include

Johann Sebastian Bach,

George Frideric Handel, and

Georg Philipp Telemann.

Classicism

The music of the

Classical Period

(1750 to 1830) looked to the art and philosophy of Ancient Greece and

Rome, to the ideals of balance, proportion and disciplined expression.

It has a lighter, clearer and considerably simpler texture, and tended

to be almost voicelike and singable. New genres were discovered. The

main style was the

homophony,

[23] where prominent

melody and

accompaniment are clearly distinct.

Importance was given to

instrumental music. It was dominated by further evolution of musical forms initially defined in the Baroque period: the

sonata, the

concerto, and the

symphony. Others main kinds were

trio,

string quartet,

serenade and

divertimento.

The sonata was the most important and developed form. Although Baroque

composers also wrote sonatas, the Classical style of sonata is

completely distinct. All of the main instrumental forms of the Classical

era were based on the dramatic structure of the sonata.

One of the most important evolutionary steps made in the Classical

period was the development of public concerts. The aristocracy would

still play a significant role in the sponsorship of musical life, but it

was now possible for composers to survive without being its permanent

employees. The increasing popularity led to a growth in both the number

and range of the orchestras. The expansion of orchestral concerts

necessitated large public spaces. As a result of all these processes,

symphonic music (including

opera,

ballet and

oratorio) became more extroverted.

The best known composers of Classicism are

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach,

Christoph Willibald Gluck,

Johann Christian Bach,

Joseph Haydn,

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart,

Ludwig van Beethoven and

Franz Schubert. Beethoven and Schubert are also considered to be composers in evolution towards Romanticism.

Romanticism

Romantic music

(c. 1810 to 1900) turned the rigid styles and forms of the Classical

era into more passionate and expressive pieces. It attempted to increase

emotional expression and power to describe deeper truths or human

feelings. The emotional and expressive qualities of music came to take

precedence over technique and tradition. Romantic composers grew in

idiosyncrasy, and went further in the syncretism of different art-forms

(such as literature), history (historical figures), or nature itself

with music. Romantic love was a prevalent theme in many works composed

during this period. In some cases the formal structures from the

classical period were preserved, but in many others existing genres,

forms, and functions were improved. Also, new forms were created that

were deemed better suited to the new subject matter.

Opera and

ballet continued to evolve.

[20]

In 1800, the music developed by

Ludwig van Beethoven and

Franz Schubert introduced a more dramatic, expressive style. In Beethoven's case,

motifs, developed organically, came to replace

melody as the most significant compositional unit. Later Romantic composers such as

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky,

Antonín Dvořák, and

Gustav Mahler used more elaborated

chords and more

dissonance to create dramatic tension. They generated complex and often much longer musical works. During Romantic period

tonality was at its peak. The late 19th century saw a dramatic expansion in the size of the

orchestra, and in the role of

concerts as part of

urban society. It also saw a new diversity in

theatre music, including

operetta, and

musical comedy and other forms of

musical theatre.

[20]

20th- and 21st-century music

With

20th-century music, there was a vast increase in music listening as the

radio gained popularity and

phonographs were used to replay and distribute music. The focus of

art music was characterized by exploration of new rhythms, styles, and sounds.

Igor Stravinsky,

Arnold Schoenberg, and

John Cage

were all influential composers in 20th-century art music. The invention

of sound recording and the ability to edit music gave rise to new

subgenre of classical music, including the

acousmatic [24] and

Musique concrète schools of electronic composition.

Jazz

evolved and became an important genre of music over the course of the

20th century, and during the second half of that century,

rock music did the same. Jazz is an American musical artform that originated in the beginning of the 20th century in

African American communities in the

Southern United States from a confluence of

African and

European music traditions. The style's

West African pedigree is evident in its use of

blue notes,

improvisation,

polyrhythms,

syncopation, and the

swung note.

[25] From its early development until the present, jazz has also incorporated music from 19th- and 20th-century

American popular music.

[26] Jazz has, from its early-20th-century inception, spawned a variety of subgenres, ranging from

New Orleans Dixieland (1910s) to 1970s and 1980s-era

jazz-rock fusion.

Rock music is a genre of

popular music that developed in the 1960s from 1950s

rock and roll,

rockabilly,

blues, and

country music.

[27] The sound of rock often revolves around the

electric guitar or acoustic guitar, and it uses a strong

back beat laid down by a

rhythm section of electric

bass guitar,

drums, and keyboard instruments such as

organ,

piano, or, since the 1970s,

analog synthesizers and digital ones and computers since the 1990s. Along with the guitar or keyboards,

saxophone and blues-style

harmonica

are used as soloing instruments. In its "purest form," it "has three

chords, a strong, insistent back beat, and a catchy melody."

[28] In the late 1960s and early 1970s, it branched out into different subgenres, ranging from

blues rock and

jazz-rock fusion to

heavy metal and

punk rock, as well as the more classical influenced genre of

progressive rock and several types of

experimental rock genres.

Performance

Main article:

Performance

Performance is the physical expression of music. Often, a musical

work is performed once its structure and instrumentation are

satisfactory to its creators; however, as it gets performed, it can

evolve and change. A performance can either be rehearsed or

improvised.

Improvisation is a musical idea created without premeditation, while

rehearsal is vigorous repetition of an idea until it has achieved

cohesion.

Musicians will sometimes add improvisation to a well-rehearsed idea to create a unique performance.

Many cultures include strong traditions of

solo and performance, such as in Indian classical music, and in the Western art-music tradition. Other cultures, such as in

Bali,

include strong traditions of group performance. All cultures include a

mixture of both, and performance may range from improvised solo playing

for one's enjoyment to highly planned and organised performance rituals

such as the modern classical concert, religious processions,

music festivals or

music competitions.

Chamber music,

which is music for a small ensemble with only a few of each type of

instrument, is often seen as more intimate than symphonic works.

Aural tradition

Many types of music, such as traditional

blues and

folk music were originally preserved in the memory of performers, and the songs were handed down

orally,

or aurally (by ear). When the composer of music is no longer known,

this music is often classified as "traditional." Different musical

traditions have different attitudes towards how and where to make

changes to the original source material, from quite strict, to those

that demand improvisation or modification to the music. A culture's

history may also be passed by ear through song.

Ornamentation

In a score or on a performer's music part, this sign indicates that the musician should perform a

trill—a rapid alternation between two notes.

Play (help·info)

Play (help·info)

The detail included explicitly in the

music notation

varies between genres and historical periods. In general, art music

notation from the 17th through the 19th century required performers to

have a great deal of contextual knowledge about performing styles. For

example, in the 17th and 18th century, music notated for solo performers

typically indicated a simple, unadorned melody. However, performers

were expected to know how to add stylistically appropriate ornaments,

such as

trills and

turns.

In the 19th century, art music for solo performers may give a general

instruction such as to perform the music expressively, without

describing in detail how the performer should do this. The performer was

expected to know how to use tempo changes,

accentuation, and

pauses

(among other devices) to obtain this "expressive" performance style. In

the 20th century, art music notation often became more explicit and

used a range of markings and annotations to indicate to performers how

they should play or sing the piece.

In

popular music

and jazz, music notation almost always indicates only the basic

framework of the melody, harmony, or performance approach; musicians and

singers are expected to know the performance conventions and styles

associated with specific genres and pieces. For example, the "

lead sheet" for a jazz tune may only indicate the melody and the chord changes. The performers in the

jazz ensemble are expected to know how to "flesh out" this basic structure by adding ornaments, improvised music, and chordal accompaniment.

Philosophy and aesthetics

Philosophy of music is the study of fundamental questions regarding

music. The philosophical study of music has many connections with

philosophical questions in

metaphysics and

aesthetics. Some basic questions in the philosophy of music are:

- What is the definition of music? (What are the necessary and sufficient conditions for classifying something as music?)

- What is the relationship between music and mind?

- What does musical history reveal to us about the world?

- What is the connection between music and emotions?

- What is meaning in relation to music?

Traditionally, the aesthetics of music explored the mathematical and

cosmological dimensions of rhythmic and harmonic organization. In the

eighteenth century, focus shifted to the experience of hearing music,

and thus to questions about its beauty and human enjoyment (

plaisir and

jouissance) of music. The origin of this philosophic shift is sometimes attributed to

Baumgarten in the 18th century, followed by

Kant.

Through their writing, the ancient term 'aesthetics', meaning sensory

perception, received its present day connotation. In recent decades

philosophers have tended to emphasize issues besides beauty and

enjoyment. For example, music's capacity to express emotion has been a

central issue.

In the 20th century, important contributions were made by

Peter Kivy,

Jerrold Levinson,

Roger Scruton, and

Stephen Davies. However, many musicians,

music critics,

and other non-philosophers have contributed to the aesthetics of music.

In the 19th century, a significant debate arose between

Eduard Hanslick, a music critic and musicologist, and composer

Richard Wagner.

Harry Partch and some other

musicologists, such as

Kyle Gann, have studied and tried to popularize

microtonal music and the usage of alternate

musical scales. Also many modern composers like

Lamonte Young,

Rhys Chatham and

Glenn Branca paid much attention to a scale called

just intonation.

It is often thought that music has the ability to affect our

emotions,

intellect, and

psychology; it can assuage our loneliness or incite our passions. The philosopher

Plato suggests in

the Republic

that music has a direct effect on the soul. Therefore, he proposes that

in the ideal regime music would be closely regulated by the state.

(Book VII)

There has been a strong tendency in the aesthetics of music to

emphasize the paramount importance of compositional structure; however,

other issues concerning the aesthetics of music include

lyricism,

harmony,

hypnotism,

emotiveness,

temporal dynamics,

resonance, playfulness, and

color (see also

musical development).

Psychology

Modern music psychology aims to explain and understand musical

behavior and

experience.

[29] Research in this field and its subfields are primarily

empirical; their knowledge tends to advance on the basis of interpretations of data collected by systematic

observation of and interaction with

human participants.

In addition to its focus on fundamental perceptions and cognitive

processes, music psychology is a field of research with practical

relevance for many areas, including music

performance,

composition,

education,

criticism, and

therapy, as well as investigations of human

aptitude,

skill,

intelligence,

creativity, and

social behavior.

Cognitive neuroscience of music

Cognitive neuroscience of music is the scientific study of

brain-based mechanisms involved in the cognitive processes underlying

music. These behaviours include music listening, performing, composing,

reading, writing, and ancillary activities. It also is increasingly

concerned with the brain basis for musical aesthetics and musical

emotion. The field is distinguished by its reliance on direct

observations of the brain, using such techniques as

functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI),

transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS),

magnetoencephalography (MEG),

electroencephalography (EEG), and

positron emission tomography (PET).

Cognitive musicology

Cognitive musicology is a branch of

cognitive science concerned with

computationally modeling musical knowledge with the goal of understanding both music and cognition.

[30] The use of computer models provides an exacting, interactive medium in which to formulate and test theories and has roots in

artificial intelligence and

cognitive science.

[31]

This interdisciplinary field investigates topics such as the

parallels between language and music in the brain. Biologically inspired

models of computation are often included in research, such as neural

networks and evolutionary programs.

[32]

This field seeks to model how musical knowledge is represented, stored,

perceived, performed, and generated. By using a well-structured

computer environment, the systematic structures of these cognitive

phenomena can be investigated.

[33]

Psychoacoustics

Psychoacoustics is the scientific study of

sound perception. More specifically, it is the branch of science studying the

psychological and

physiological responses associated with sound (including

speech and music). It can be further categorized as a branch of

psychophysics.

Evolutionary musicology

Evolutionary musicology concerns the "origins of music, the question

of animal song, selection pressures underlying music evolution", and

"music evolution and human evolution".

[34] It seeks to understand music perception and activity in the context of

evolutionary theory.

Charles Darwin speculated that music may have held an adaptive advantage and functioned as a

protolanguage,

[35] a view which has spawned several competing theories of music evolution.

[36][37][38] An alternate view sees music as a by-product of

linguistic evolution; a type of "auditory cheesecake" that pleases the senses without providing any adaptive function.

[39] This view has been directly countered by numerous music researchers.

[40][41][42]

Culture in music cognition

An individual's

culture or

ethnicity plays a role in their

music cognition, including their

preferences,

emotional reaction, and

musical memory.

Musical preferences are biased toward culturally familiar musical

traditions beginning in infancy, and adults' classification of the

emotion of a musical piece depends on both culturally specific and

universal structural features.

[43][44]

Additionally, individuals' musical memory abilities are greater for

culturally familiar music than for culturally unfamiliar music.

[45][46]

Sociology

This Song Dynasty (960–1279) painting, entitled the "Night

Revels of Han Xizai," shows Chinese musicians entertaining guests at a

party in a 10th-century household.

Many ethnographic studies demonstrate that music is a participatory, community-based activity.

[47][48]

Music is experienced by individuals in a range of social settings

ranging from being alone to attending a large concert, forming a

music community,

which cannot be understood as a function of individual will or

accident; it includes both commercial and non-commercial participants

with a shared set of common values. Musical performances take different

forms in different cultures and socioeconomic milieus. In Europe and

North America, there is often a divide between what types of music are

viewed as a "

high culture" and "

low culture."

"High culture" types of music typically include Western art music such

as Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and modern-era symphonies, concertos,

and solo works, and are typically heard in formal concerts in concert

halls and churches, with the audience sitting quietly in seats.

Other types of music—including, but not limited to, jazz, blues,

soul, and

country—are

often performed in bars, nightclubs, and theatres, where the audience

may be able to drink, dance, and express themselves by cheering. Until

the later 20th century, the division between "high" and "low" musical

forms was widely accepted as a valid distinction that separated out

better quality, more advanced "art music" from the popular styles of

music heard in bars and dance halls.

However, in the 1980s and 1990s, musicologists studying this

perceived divide between "high" and "low" musical genres argued that

this distinction is not based on the musical value or quality of the

different types of music.

[citation needed] Rather, they argued that this distinction was based largely on the

socioeconomics standing or

social class of the performers or audience of the different types of music.

[citation needed]

For example, whereas the audience for Classical symphony concerts

typically have above-average incomes, the audience for a rap concert in

an inner-city area may have below-average incomes.

[citation needed]

Even though the performers, audience, or venue where non-"art" music is

performed may have a lower socioeconomic status, the music that is

performed, such as blues, rap,

punk,

funk, or

ska may be very complex and sophisticated.

When composers introduce styles of music that break with convention,

there can be a strong resistance from academic music experts and popular

culture. Late-period Beethoven string quartets, Stravinsky

ballet scores,

serialism,

bebop-era jazz, hip hop, punk rock, and

electronica have all been considered non-music by some critics when they were first introduced.

[citation needed] Such themes are examined in the

sociology of music. The sociological study of music, sometimes called

sociomusicology, is often pursued in departments of sociology, media studies, or music, and is closely related to the field of

ethnomusicology.

Media and technology

The music that composers make can be heard through several

media;

the most traditional way is to hear it live, in the presence of the

musicians (or as one of the musicians), in an outdoor or indoor space

such as an amphitheatre,

concert hall,

cabaret room or

theatre. Live music can also be broadcast over the

radio,

television or the

Internet.

Some musical styles focus on producing a sound for a performance, while

others focus on producing a recording that mixes together sounds that

were never played "live." Recording, even of essentially live styles,

often uses the ability to edit and splice to produce recordings

considered better than the actual performance.

As

talking pictures

emerged in the early 20th century, with their prerecorded musical

tracks, an increasing number of moviehouse orchestra musicians found

themselves out of work.

[49] During the 1920s live musical performances by orchestras,

pianists, and

theater organists were common at first-run theaters.

[50] With the coming of the talking motion pictures, those featured performances were largely eliminated. The

American Federation of Musicians

(AFM) took out newspaper advertisements protesting the replacement of

live musicians with mechanical playing devices. One 1929 ad that

appeared in the

Pittsburgh Press

features an image of a can labeled "Canned Music / Big Noise Brand /

Guaranteed to Produce No Intellectual or Emotional Reaction Whatever"

[51]

Since legislation introduced to help protect performers, composers, publishers and producers, including the

Audio Home Recording Act of 1992 in the United States, and the 1979 revised

Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works

in the United Kingdom, recordings and live performances have also

become more accessible through computers, devices and Internet in a form

that is commonly known as

Music-On-Demand.

In many cultures, there is less distinction between performing and

listening to music, since virtually everyone is involved in some sort of

musical activity, often communal. In industrialized countries,

listening to music through a recorded form, such as

sound recording or watching a

music video, became more common than experiencing live performance, roughly in the middle of the 20th century.

Sometimes, live performances incorporate prerecorded sounds. For example, a

disc jockey uses

disc records for

scratching,

and some 20th-century works have a solo for an instrument or voice that

is performed along with music that is prerecorded onto a tape.

Computers and many

keyboards can be programmed to produce and play

Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) music. Audiences can also

become performers by participating in

karaoke,

an activity of Japanese origin centered on a device that plays

voice-eliminated versions of well-known songs. Most karaoke machines

also have video screens that show lyrics to songs being performed;

performers can follow the lyrics as they sing over the instrumental

tracks.

Internet

The advent of the

Internet has transformed the experience of music, partly through the increased ease of access to music and the increased choice.

Chris Anderson, in his book

The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More, suggests that while the economic model of

supply and demand describes scarcity, the Internet retail model is based on abundance.

Digital storage

costs are low, so a company can afford to make its whole inventory

available online, giving customers as much choice as possible. It has

thus become economically viable to offer products that very few people

are interested in. Consumers' growing awareness of their increased

choice results in a closer association between listening tastes and

social identity, and the creation of thousands of

niche markets.

[52]

Another effect of the Internet arises with

online communities like

YouTube and

Facebook, a

social networking service.

Such sites simplify connecting with other musicians, and greatly

facilitate the distribution of music. Professional musicians also use

YouTube as a free publisher of promotional material. YouTube users, for

example, no longer only download and listen to

MP3s, but also actively create their own. According to

Don Tapscott and

Anthony D. Williams, in their book

Wikinomics, there has been a shift from a traditional consumer role to what they call a "

prosumer" role, a consumer who both creates and consumes. Manifestations of this in music include the production of

mashes,

remixes, and music videos by fans.

[53]

Business

Main article:

Music industry

The music industry refers to the business industry connected with the

creation and sale of music. It consists of record companies,

labels and

publishers

that distribute recorded music products internationally and that often

control the rights to those products. Some music labels are "

independent," while others are subsidiaries of larger corporate entities or international

media groups.

In the 2000s, the increasing popularity of listening to music as

digital music files on MP3 players, iPods, or computers, and of trading

music on file sharing sites or buying it online in the form of digital

files had a major impact on the traditional music business. Many smaller

independent CD stores went out of business as music buyers decreased

their purchases of CDs, and many labels had lower CD sales. Some

companies did well with the change to a digital format, though, such as

Apple's

iTunes, an online store that sells digital files of songs over the Internet.

Education

Non-professional

A Suzuki violin recital with students of varying ages.

The incorporation of music training from

preschool to

post secondary education is common in North America and Europe. Involvement in music is thought to teach basic skills such as concentration,

counting, listening, and

cooperation while also promoting understanding of

language, improving the ability to

recall information, and creating an environment more conducive to learning in other areas.

[54] In

elementary schools, children often learn to play instruments such as the

recorder,

sing in small choirs, and learn about the history of Western art music.

In secondary schools students may have the opportunity to perform some

type of musical ensembles, such as choirs,

marching bands,

concert bands,

jazz bands, or orchestras, and in some school systems, music classes may be available. Some students also take private

music lessons

with a teacher. Amateur musicians typically take lessons to learn

musical rudiments and beginner- to intermediate-level musical

techniques.

At the

university level, students in most arts and

humanities programs can receive

credit for taking music courses, which typically take the form of an overview course on the

history of music, or a

music appreciation

course that focuses on listening to music and learning about different

musical styles. In addition, most North American and European

universities have some type of musical ensembles that non-music students

are able to participate in, such as choirs, marching bands, concert

bands, or orchestras. The study of Western art music is increasingly

common outside of North America and Europe, such as the

Indonesian Institute of the Arts in

Yogyakarta,

Indonesia,

or the classical music programs that are available in Asian countries

such as South Korea, Japan, and China. At the same time, Western

universities and colleges are widening their curriculum to include music

of non-Western cultures, such as the

music of Africa or Bali (e.g.

Gamelan music).

Academia

Musicology is the study of the subject of music. The earliest definitions defined three sub-disciplines:

systematic musicology,

historical musicology, and comparative musicology or

ethnomusicology.

In contemporary scholarship, one is more likely to encounter a division

of the discipline into music theory, music history, and

ethnomusicology. Research in musicology has often been enriched by

cross-disciplinary work, for example in the field of

psychoacoustics.

The study of music of non-western cultures, and the cultural study of

music, is called ethnomusicology. Students can pursue the undergraduate

study of musicology, ethnomusicology,

music history, and music theory through several different types of degrees, including a

B.Mus,

a B.A. with concentration in music, a B.A. with Honors in Music, or a

B.A. in Music History and Literature. Graduates of undergraduate music

programs can go on to further study in music graduate programs.

Graduate degrees include the

Master of Music, the

Master of Arts, the

Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) (e.g., in musicology or music theory), and more recently, the

Doctor of Musical Arts,

or DMA. The Master of Music degree, which takes one to two years to

complete, is typically awarded to students studying the performance of

an instrument, education, voice or composition. The Master of Arts

degree, which takes one to two years to complete and often requires a

thesis, is typically awarded to students studying musicology, music history, or music theory.

Undergraduate university degrees in music, including the

Bachelor of Music, the Bachelor of Music Education, and the

Bachelor of Arts

(with a major in music) typically take three to five years to complete.

These degrees provide students with a grounding in music theory and

music history, and many students also study an instrument or learn

singing technique as part of their program.

The PhD, which is required for students who want to work as

university professors in musicology, music history, or music theory,

takes three to five years of study after the Master's degree, during

which time the student will complete advanced courses and undertake

research for a dissertation. The DMA is a relatively new degree that was

created to provide a credential for professional performers or

composers that want to work as university professors in musical

performance or composition. The DMA takes three to five years after a

Master's degree, and includes advanced courses, projects, and

performances. In Medieval times, the study of music was one of the

Quadrivium of the seven

Liberal Arts and considered vital to higher learning. Within the quantitative Quadrivium, music, or more accurately

harmonics, was the study of rational proportions.

Zoomusicology is the study of the music of non-human animals, or the musical aspects of sounds produced by non-human animals. As

George Herzog (1941) asked, "do animals have music?"

François-Bernard Mâche's

Musique, mythe, nature, ou les Dauphins d'Arion (1983), a study of "ornitho-musicology" using a technique of

Nicolas Ruwet's

Langage, musique, poésie (1972)

paradigmatic segmentation analysis, shows that

bird songs

are organised according to a repetition-transformation principle.

Jean-Jacques Nattiez (1990), argues that "in the last analysis, it is a

human being who decides what is and is not musical, even when the sound

is not of human origin. If we acknowledge that sound is not organised

and conceptualised (that is, made to form music) merely by its producer,

but by the mind that perceives it, then music is uniquely human."

Music theory is the study of music, generally in a highly technical

manner outside of other disciplines. More broadly it refers to any study

of music, usually related in some form with compositional concerns, and

may include

mathematics,

physics, and

anthropology. What is most commonly taught in beginning music theory classes are guidelines to write in the style of the

common practice period, or

tonal music. Theory, even of music of the common practice period, may take many other forms.

Musical set theory is the application of mathematical

set theory to music, first applied to

atonal music.

Speculative music theory, contrasted with

analytic music theory, is devoted to the analysis and synthesis of music materials, for example

tuning systems, generally as preparation for composition.

Ethnomusicology

In the West, much of the history of music that is taught deals with

the Western civilization's art music. The history of music in other

cultures ("

world music"

or the field of "ethnomusicology") is also taught in Western

universities. This includes the documented classical traditions of Asian

countries outside the influence of Western Europe, as well as the folk

or indigenous music of various other cultures. Popular styles of music

varied widely from culture to culture, and from period to period.

Different cultures emphasised different

instruments,

or techniques, or uses for music. Music has been used not only for

entertainment, for ceremonies, and for practical and artistic

communication, but also for

propaganda.

There is a host of music classifications, many of which are caught up

in the argument over the definition of music. Among the largest of

these is the division between classical music (or "art" music), and

popular music (or

commercial music – including

rock music,

country music, and

pop music). Some genres do not fit neatly into one of these "big two" classifications, (such as folk music, world music, or jazz music).

As world cultures have come into

greater contact, their indigenous musical styles have often merged into new styles. For example, the United States

bluegrass style contains elements from

Anglo-

Irish,

Scottish, Irish,

German

and African instrumental and vocal traditions, which were able to fuse

in the United States' multi-ethnic society. Genres of music are

determined as much by tradition and presentation as by the actual music.

Some works, like

George Gershwin's

Rhapsody in Blue, are claimed by both jazz and classical music, while Gershwin's

Porgy and Bess and

Leonard Bernstein's

West Side Story are claimed by both opera and the

Broadway musical tradition. Many current music festivals celebrate a particular musical genre.

Indian music,

for example, is one of the oldest and longest living types of music,

and is still widely heard and performed in South Asia, as well as

internationally (especially since the 1960s). Indian music has mainly

three forms of classical music,

Hindustani,

Carnatic, and

Dhrupad

styles. It has also a large repertoire of styles, which involve only

percussion music such as the talavadya performances famous in

South India.

Music therapy

Main article:

Music therapy

is an interpersonal process in which the therapist uses music and all

of its facets—physical, emotional, mental, social, aesthetic, and

spiritual—to help clients to improve or maintain their health. In some

instances, the client's needs are addressed directly through music; in

others they are addressed through the relationships that develop between

the client and therapist. Music therapy is used with individuals of all

ages and with a variety of conditions, including: psychiatric

disorders, medical problems, physical handicaps, sensory impairments,

developmental disabilities, substance abuse, communication disorders,

interpersonal problems, and aging. It is also used to: improve learning,

build self-esteem, reduce stress,

support physical exercise, and facilitate a host of other health-related activities.

One of the earliest mentions of music therapy was in

Al-Farabi's (c. 872 – 950) treatise

Meanings of the Intellect, which described the

therapeutic effects of music on the

soul.

[55][verification needed] Music has long been used to help people deal with their emotions. In the 17th century, the scholar

Robert Burton's

The Anatomy of Melancholy argued that music and dance were critical in treating

mental illness, especially

melancholia.

[56]

He noted that music has an "excellent power ...to expel many other

diseases" and he called it "a sovereign remedy against despair and

melancholy." He pointed out that in Antiquity, Canus, a Rhodian fiddler,

used music to "make a melancholy man merry, ...a lover more enamoured, a

religious man more devout."

[57][58][59] In November 2006, Dr. Michael J. Crawford

[60] and his colleagues also found that music therapy helped

schizophrenic patients.

[61] In the

Ottoman Empire, mental illnesses were treated with music.

[62]